A word on Angular route resolvers – and a praise for Reactive Programming

We need to talk about Angular route resolvers. Resolvers are services used by the Angular router to retrieve (asynchronous) data for us during navigation. The resolved data is available synchronously when the component starts.

If you never heard about resolvers, you are fine! Have you ever used them? This is okay, but you should probably avoid this.

In this post I want to highlight why resolvers are not the perfect means for resolving async data. I want to point out how there is always a way around them and how Reactive Programming in Angular can brighten up your day. In fact, this blog post is sort of a speech of praise for Reactive Programming in Angular.

The anatomy of resolvers

Before we start, let's talk about what resolvers are and how we implement them. If you already used them before, you can probably skip this intro.

Technically speaking, a resolver is an Angular service that encapsulates async operations.

The Angular router utilizes this service to resolve those operations during navigation and make the data available for the routed components.

A resolver always follows a specific structure: it's a class with a resolve() method.

This is the place where we define all necessary operations and return the result – usually as an Observable.

The resolve() method will be called by the router with some arguments, from which we can get information about the route that will be navigated to.

The following example shows a resolver that loads a book by a specific key that comes from a route parameter (in our case a unique "International Standard Book Number" (ISBN)).

import { Injectable } from '@angular/core';

import { Resolve, ActivatedRouteSnapshot, RouterStateSnapshot } from '@angular/router';

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class BookResolverService implements Resolve<Book> {

constructor(private bs: BookStoreService) { }

resolve(

route: ActivatedRouteSnapshot,

state: RouterStateSnapshot

): Observable<Book> {

return this.bs.getOne(route.paramMap.get('isbn'));

}

}

A service alone is not enough – we also need someone to call it. Since the resolver should be invoked by the router, the right place to insert it is our route configurations. We provide an object here with at least one resolver:

{

path: 'mypath',

component: MyComponent,

resolve: {

book: BookResolverService

}

}

When this route is being requested, the router automatically invokes the resolve() method of the resolver, subscribes to the Observable and makes the resulting data available for the component synchronously.

Within the component, we can use the ActivatedRoute service to get access to the data:

// ...

@Component({ /* ... */ })

export class MyComponent {

constructor(private route: ActivatedRoute) { }

ngOnInit() {

this.book = this.route.snapshot.data.book;

}

}

The User Experience problem with resolvers

Resolvers are very straightforward to use, since they are just services that are automatically being called by the router. However, we need to keep in mind an important detail: The router calls the resolver when the route is being requested – and then waits for the data to be resolved before the route is actually being activated.

Now imagine a long running HTTP request. After clicking a link in our application, the HTTP request starts. The routing will not be finished before the HTTP response comes back. Thus, if the HTTP takes 5 seconds, it will also take 5 seconds for the routing to complete. If you are like me, you will have hit the button another 3 times within that time. 😉

This behavior completely breaks the idea of a Single-Page Application: An SPA should always react fast and load the necessary data asynchronously at runtime. With the behavior described – click, wait, continue – we are back to the user experience of a classical server-only rendered page like 15 years ago. Not good. And here we are with the problematic UX resolvers bring us. Try this out in the demo!

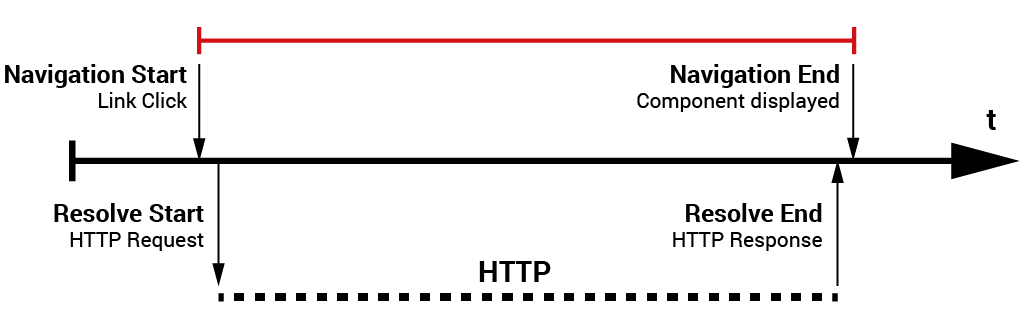

To make things clearer let's also take a look at a time diagram. The red bracket marks the time between navigation start and end. You can clearly see that the HTTP request blocks the navigation:

What we rather want to do is to show the requested page immediately after the click, but without the data. Finally, when the data is available, we render the complete page. Resolvers are not the right means for this. But maybe we can think of another approach?

A life without resolvers: Observables everywhere

The solution I want to point out here is pragmatic, but goes back to the roots: Don't use resolvers. Instead, you can go the "normal" way without any real friction. There is nothing wrong with handling Observables within components. Angular is a reactive framework and highly encourages you to work with reactive streams wherever suitable.

Thus, the best way of doing is to make Observables available from your service and subscribe to them in your component:

// ...

@Component({ /* ... */ })

export class MyComponent {

books: Book[];

constructor(private bs: BookStoreService) { }

ngOnInit() {

this.bs.getAll()

.subscribe(books => this.books = books);

}

}

... or, even better, use the AsyncPipe to resolve the data directly within the template, so you don't need to care about subscription management in the component at all:

// ...

@Component({ /* ... */ })

export class MyComponent {

books$: Observable<Book[]>;

constructor(private bs: BookStoreService) { }

ngOnInit() {

this.books$ = this.bs.getAll();

}

}

<div *ngFor="let b of books$ | async">

{{ book.title }}

</div>

The power of Observables

I want to emphasize the key point once more: When using resolvers, the route will be loaded after the asynchronous data from the resolver has been retrieved, or in other words: The router will wait for the resolver to finish.

This leads to the more or less lucky situation that we have all the data synchronously available at the runtime of the component. And as you well know: Working with synchronous data is way easier than fiddling around with async stuff. You don't need to handle Observables and you can just work with the data as intended. If you feel this way, please always keep one question in mind: Why do I need this? Is the UX flaw (as described above) really worth the "easier" code?

At first sight, reactive streams seem to be overly complicated – in fact this was my initial feeling when I first dealt with RxJS a few years back. Observables are the "final enemy" for many people starting with Angular. And indeed: to understand reactive programming you need a little change of thinking: Embrace functional and declarative programming, say goodbye to the commonly known imperative way. It needs a lot of practice and it is perfectly fine if you still struggle with Observables and all the operators. But once you're there you will see that Angular itself is a highly reactive framework. Everything that happens somewhere can be interpreted as a stream of events or data – or even more abstract: a set of values. And thinking of everything as a stream makes it easier to migrate to some sort of reactive state management later, like the popular NgRx.

What is more, sometimes it is impossible to avoid Observables in Angular.

Imagine, you want to retrieve a route parameter that changes during the runtime of a component – you need ActivatedRoute.paramMap for that, which is an Observable.

If you want to react to changes in form values, you need to use FormGroup.valueChanges.

And there are a lot more! Even the EventEmitter that we use for component outputs is an Observable internally.

Don't be scared of Observables!

Observables in the wild: An example

To point out how Observables cross our way in the daily dev life, I want to get back to the example from above. Instead of retrieving a list of books, we now want to get one specific book whose ISBN comes from a route parameter.

We use the ActivatedRoute service as usual and get a stream of changing route params.

Instead of subscribing to that observable (we should avoid that anyway and always use the AsyncPipe), we transform the data stream even further.

For every ISBN that changes in the route, we want to retrieve the corresponding book from the API.

We can use the switchMap() operator here and transform each ISBN to the retrieved book.

Thus, we get a stream of single books which we can simply display in the template.

// ...

@Component({ /* ... */ })

export class MyComponent {

book$: Observable<Book>;

constructor(private bs: BookStoreService, private route: ActivatedRoute) { }

ngOnInit() {

this.book$ = this.route.paramMap(

map(params => params.get('isbn')),

switchMap(isbn => this.bs.getOne(isbn))

);

}

}

Note that we used the

switchMap()operator intentionally here: When the route changes, we want to cancel the running request. However, please do not useswitchMap()blindly but also consider its siblingsconcatMap(),mergeMap()andexhaustMap().

Child components to the rescue: Container and Presentational Components

Observables are great, but even when we deal a lot with Observables in our components, that doesn't mean we can't have any data synchronously available without a callback.

This is possible with a closer look at the component tree: When we put a child component into our template and pass data to it via property binding, this data is available synchronously after the first ngOnChanges() of the child component – which means we can directly access it within ngOnInit().

Component communication is the key!

If we think this even further, we can separate our components by their role and divide them into Containers and Presentational Components.

Let's talk about this pattern!

The most pragmatic of those two component roles is the Presentational Component. It is only concerned with displaying data and capturing things from the user through the UI, like events and data. Presentationals are completely "dumb" in the sense of that they have no external dependencies. What is more, they neither care about where the data comes from nor what happens to the events they push to their parent. All communication is done via Inputs and Output and usually there are no services involved.

A presentational component never comes alone, but will always be orchestrated by another component – either another presentational or a container. Containers are components as well, but with very little own markup. Instead, containers resemble the interface to the rest of the application: They communicate with services, the router or the NgRx store and thus, potentially perform side-effects. They pass data to presentationals (via property binding) and receive events from them (via event binding) which they can forward to the application. Containers are sometimes referred to as "smart components" (as opposed to "dumb"), because they have the knowledge of the actual wiring. Presentationals are easily reusable, while containers often are very specific for a certain page or application slice.

This pattern is very generic and not made specifically for Angular – instead, it has evolved in the React community first. You can read more about the ideas in a blog post by Dan Abramov.

My advice: Take the Container and Presentational pattern as a guideline! Basically, it is all about being aware of what a component's role is: Does it display data or does it do the data handling? Try not to mix those concerns.

Some people suggest separating Containers and Presentational Components in separate folders in the file system. You can do this, but in my opinion, it's already a step forward if you are aware of what a component does. A component should always be as "dumb" as possible and as "smart" as necessary. Thus, you should strive to create a lot of dumb components, as they are easily testable, interchangable and reusable.

Why all the theory? Child components in action

After clearing up the idea of component roles, let's get back to the problem point: Resolvers bring data to the component synchronously, while Observables always need a subscribe callback and are potentially asynchronous, especially with HTTP.

If we follow the Containers and Presentationals pattern, we always build a tree of nested components. The topmost container will retrieve some data through a service. As soon as the data is available, it will render a child component and pass the data to it via property binding. That means, at runtime of the child component, the data is available synchronously – even if it originally comes from an async data source! The key point is to not render the child before the data has been retrieved.

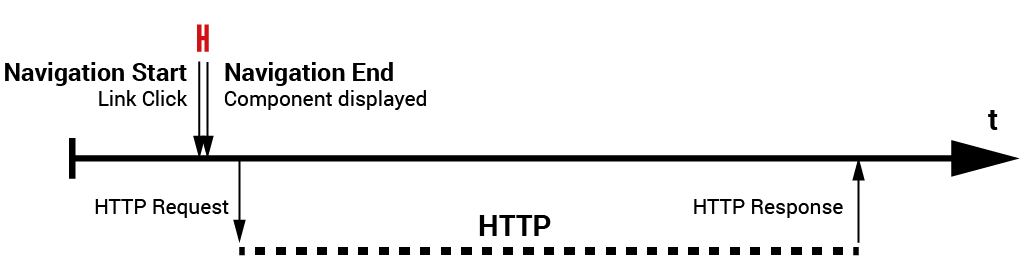

With this idea in mind we can update the timeline from above.

The red bracket (that looks like a H)shows the time between navigation start and end again.

You can clearly see that the time between click and routing is literally zero now – the routing start and end happen directly after each other, without any delay. We still need to wait for the HTTP request to complete, but the routed component is already visible and we can show some meaningful content to the user – instead of letting them wait without any feedback. Ghost elements can help here to indicate that something is in progress.

Though it sounds a bit complicated at first glance, the idea described is relatively easy to implement, as it just makes use of standard Angular concepts.

First, we use the fabulous AsyncPipe to resolve the Observable in our container component.

We then pass it to a presentational component which we don't render before the Observable emitted some data – using ngIf!

At runtime of the child component, the data will be synchronously available in its ngOnInit(). That's cool!

<ng-container *ngIf="book$ | async as book">

<my-book-details [book]="book">

</ng-container>

The component <my-book-details> is a simple presentational component that just displays one book.

However, we can extend this idea to whatever complexity we need.

Resolving multiple streams

In the previous example we resolved exactly one Observable using the AsyncPipe.

But what happens when it comes to multiple data sources?

If we used multiple resolvers, the router would wait for all of them to finish so that multiple data sets would be available for the component.

A solution without resolvers is a bit more complex but not impossible. We can use the exact same syntax, but put together multiple template expressions in an object:

<ng-container *ngIf="{

book: book$ | async,

user: user$ | async

} as data">

<my-book-details [book]="data.book" [user]="data.user">

</ng-container>

However, this solution is not complete... Do you spot the problematic point?

ngIf always evaluates an object as truthy, so the child component will always be displayed.

We could avoid this with an additional ngIf on the child component element like this:

<ng-container *ngIf="{

book: book$ | async,

user: user$ | async

} as data">

<my-book-details *ngIf="data.book && data.user" [book]="data.book" [user]="data.user">

</ng-container>

This is quite verbose, though, and puts too much logic into the template.

A better approach therefore would be to combine the different Observable streams to one single stream in the component class using combineLatest.

We then can use the ngIf way as usual and subscribe to one Observable only.

this.viewModel$ = combineLatest([book$, user$]).pipe(

map(([book, user]) => ({ book, user }))

);

<ng-container *ngIf="viewModel$ | async as data">

<my-book-details [book]="data.book" [user]="data.user">

</ng-container>

This whole topic of how we can resolve multiple Observables in a component is already worth a whole blog post. There has been a discussion on Twitter recently about how to do this properly and how a suitable syntax should be formed.

So far so good... But why resolvers?

This blog post took a little turn! You can see that there is always a way to avoid resolvers. Leveraging reactive programming in Angular opens the door to a handful of patterns for Observable handling.

But what about resolvers then? You are right if you wonder what they are actually be good for. It's not easy to find a valid use case that beats the reactive approach. However, after some discussions we came up with a potentially valid one – for academic purpose only! 😇

Using a resolver is fine when the data is available instantly. So think about data we need at many places in our application, that should be available once the component starts and that doesn't take much time to load: Configuration objects! I want to outline this specific idea with an example. First, we need a service that retrieves config data from a server via HTTP:

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class ConfigService {

getConfig(): Observable<AppConfig> {

return this.http.get(/* ... */);

}

}

Of course, this HTTP request takes some time!

We don't want to perform the request on every route change, but only once, when the application starts.

To do so, we can use a caching mechanism by RxJS: the shareReplay() operator.

It subscribes to the source (the HTTP request) only once and multicasts the response to all subscribers.

It also buffers the response and replays is to future subscribers.

That means, whenever we subscribe to the resulting Observable, we either perform a HTTP request and get a fresh config object from the server – or we get the cached one.

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class ConfigService {

config$ = this.getConfig().pipe(

shareReplay(1)

);

private getConfig(): Observable<AppConfig> {

return this.http.get(/* ... */);

}

}

The corresponding resolver is relatively easy to implement since it just returns the config$ Observable from the service:

@Injectable({ providedIn: 'root' })

export class ConfigResolverService implements Resolve<AppConfig> {

constructor(private cs: ConfigService) { }

resolve(): Observable<AppConfig> {

return this.cs.config$;

}

}

All routes that use this resolver will now have the config object available in their route data. When loading the first route, the HTTP request will be performed, but only once for the lifetime of the application.

Of course, this doesn't come without caveats:

Since resolvers are used by the router, the route data can only be accessed by routed components and not by the AppComponent.

And if we take a closer look, we can see: We could just inject the ConfigService into any component and use the config$ Observable directly.

So no actual need for resolvers here? 😇

You can play around with this example in a StackBlitz project:

A word on resolvers: Summary

Resolvers are cool, but the use cases are very rare.

When it comes to retrieving async data via resolvers, like HTTP requests, the User Experience suffers a lot: Resolvers wait for the async tasks to finish, before the routing continues.

That means, you should only use resolvers for operations that are predictably fast – so your users don't need to wait.

However, with the ideas of Reactive Programming, we can apply a variety of reactive patterns to our code that make resolvers superfluous.

Observables are powerful and you should use that power!

An Observable can easily be resolved directly within the component using the AsyncPipe.

That's also possible with multiple Observables, by combining them into one single stream of values.

If you still need the data synchronously and without Observables, you can use child components and pass the values to them via property bindings.

You can see that there is always a way around resolvers. If you have resolvers in your code base and it works well – great! If you think about introducing resolvers, please also evaluate a reactive approach – because Reactive Programming is a lot of fun! 😍

Special thanks to Johannes Hoppe for the technical review and to Rhianna Masson for the native language review!

Header image: Photo by Yuting Gao from Pexels, modified

Keywords:AngularRouterResolverData LoadingData ProviderRxJSReactive ProgrammingObservables

Suggestions? Feedback? Bugs? Please